By Nick Metzger & Lee Rice Epstein

Featuring Damon Smith

A continuation of the conversation between Lee, Damon Smith, and myself talking about the recent Balance Point Acoustics releases among many other things. Also be sure to catch Smith on tour this April & May in a trio with Jason Stein and Adam Shead whose new album Volumes & Surfaces we discuss below.

Sarah Ruth Alexander/Damon Smith - God Made My Soul an Ornament (Balance Point Acoustics, 2021)

DS: I went to Texas in I think, 2017 or something for a family health situation, and my girlfriend was at Harvard working on the Bauhaus show, the Bauhaus Centennial Show, and so she had that to do and when I didn't have gigs, I was pretty free. And I've been teaching remotely for years already by that point. So I could just go to Texas. So I went to Texas to kind of take care of her mom and be with her mom after she just got out of the hospital and stuff. And I brought my travel bass so I could practice because I was there for like two and a half weeks. The first time Stephan Gonzalez had a music series and Stephan wasn't available Sarah took it over and got in touch with me, found out I was there, and I didn't know when I went down at this time that I'd be able to play at all. She organized some concerts for me in Denton and in Dallas then I met and heard her on one of those nights. Then we got to know each other, she's got a lot of similar interests, there's a lot of similarities, and she gets a lot from literature and visual art and other things like that. And there's a lot of similar tastes that we have and then a lot of different tastes, which makes it interesting. But the fact that a lot of her influencers are coming from these other art forms was a really great place for us to connect. So we did several duo concerts, and then we made this duo recording, like two in the morning at North Texas State and it had been sitting for a while, and we wanted to do it.

She had been reading the Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa, which is a big one for me, and it turned out one of the interesting things is that my very first bass guitar teacher (Chris Daniels) was a student of Jaco Pastorius, which I thought was cool. But then I sort of lost touch with him, and then when I got in touch with him again, it turned out that he had learned Portuguese from working in kitchens and became one of the primary translators of Fernando Pessoa’s Heteronyms. He's got two books out and he gave me a Pessoa translation. I thought that was really exciting. It's a bold title in a way and I don't necessarily have a spiritual practice. I'm more like Barre Phillips who said, my religion is bass. I feel like art is a place where we can try to hover above our humanity and petty human squabbles rather than wallowing in them. I guess that can be thought of as a spiritual place, but I think of it as more of a subconscious space or whatever. So I'm not so much into God or souls necessarily, but I love this title. Ernesto Montiel is also a great musician, and he had all this beautiful artwork. And again, someone who I've talked to a lot about art and music and literature and these other things, and we are able to get this sculpture from him for the cover. So the design and the title of this one, not just the music, I love the music. Playing with Sarah, it's different every time. And more than anything, it embodies the concept that Bill Dixon used to talk about where he said each person is their own Orchestra. There's this architectural breadth between her and I where it's almost like anything could happen. There's the percussion and other instruments that she plays, like the dulcimer. But of course, it's really grounded in her beautiful voice, this pure classical voice, and everything hangs off of that thread, on this purity of the voice that she brings, it's so striking. But she doesn't overuse it either. I think there's just this breadth of playing with her in a duo that I feel like I feel like you've probably done ten or twelve concerts together by now as a duo, maybe more, maybe less, but we did a little tour last summer, and that's a lot for improvised music, and then each one is completely different and has a different range and a different way of doing things together. We've got some things planned for this year hopefully. We're talking about doing some stuff.

NM: This is another album that stands out like the Eternity Cult, it’s a lot different than the other ones. And to your point, she does a great job with all the different instruments and voice and contraptions and things. For it being a duo album, there's a lot of information there.

LRE: Going back to Kowald for a minute, he seemed to never stop exploring different modalities, different groups. He was constantly trying working with new players and creating work for dance, obviously, also. You also seem similarly interested in exploring new sounds that are exciting to you. Because I agree with Nick, this album. It was sort of interesting to put this one on and be like, wait a minute…(laughs)

DS: Yeah, definitely. When I heard Sarah for the first time, I was like, yeah, this is somebody doing original work. I want to play with her. It was the same kind of feeling as when I heard Sandy, honestly. She's got some great recordings, which I would recommend tracking down. There's one called Words on the Wind. It's about the Panhandle of Texas. It's amazing out, super bleak and beautiful. When I heard her. I was like, well, this is original work, and this is something that's important.

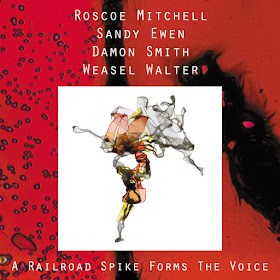

Mitchell/Ewen/Smith/Walter - A Railroad Spike Forms the Voice (ugEXPLODE, 2021)

DS: That whole thing happened because of Sandy. One of the last things I did in the Bay Area was a collaboration with a dancer named Micaela Gardner and a filmmaker Darren Hawk. And that's on YouTube somewhere. But we did these outdoor bass and dance pieces with the filmmaker kind of involved as an equal partner. And when I got to Houston, there was a dance film festival, and somebody knew that I had this film. I forget who it was. It was someone in Houston. And they said I should apply for this festival with that film, so I did and I got onto the festival. And then Sandy has a long term project with a belly dancer named Yet Torres, so I first saw her on film. I hadn't met her yet. And I was like, Whoa, that's original. I want to play with her. And so we started to play together in Houston, she was much younger than me. She's much younger than me. I think she's twelve years younger or something. But I started improvised music in my 20s, and she started it in high school. She had Keith Rowe workshops in high school. She was already a lot more experienced than your average person in her mid 20s at this music. When I started to work with her in Houston it was basically side by side. We were organizing things together, we were doing projects together, and of course I had a few more connections because I've been out in the world a little longer and stuff like that. I knew Roscoe just from being at Mills. I wasn't at Mills, but he had an Orchestra piece and Steve Cowert, one of the Mills professors, brought in Weasel and I to play in this Orchestra. He said ‘hey, do you want to come play in this Roscoe thing?’ and we're like, yeah! (laughs) And the funny thing, the other piece on the program was In C, and Weasel did the marimba parts for In C, and he did a fantastic job. And that was also an eye opening moment with Weasel. We had been working together for a bit, but then watching him just kill it on the In C part, even though it's fairly simple, it was still like Weasel Walter. It just expanded what we could do together. Roscoe came through Dave's organization, Nameless Sound, David Dove's organization and there was a workshop, and what we do in Houston, the workshops are free, and we'd all do it no matter who it was. We'd all come to the workshop because it was a musical thing, but it was also a social thing. We're all friends, and we're all going to come and come together at the Roscoe Mitchell workshop. So we're doing the workshop, And he's not really impressed with anyone except Sandy, he really loved what she was doing. And he said to a saxophone player, why don't you listen to her and try to play something like her? I could listen to what she's doing all day. So he heard what everybody else hears. So then after the workshop he said, hey, is there a beer around? So I get him a beer, and we're having a beer together and then he asked, what are you and Weasel doing? I said, oh, we just did an album with this guitar player. And he said, well, I'd love to hear that. We sent him the album, and he really liked it. So, Sandy is the reason why Roscoe knew me and Weasel and wanted to work with us. Obviously, he spent a lot of time talking to us, and there was a nice personal connection and everything, but there was no sense that Weasel and I were going to play with him until this.

And we got a gig at a place that has a really great chef. Paul Canales has a restaurant called Duende. It just reopened in Oakland, and he's been a huge fan of the music. He made dinner for Giani Gebbia and I in the 90s, like a big fancy dinner with Pigeon and all this great stuff. And he's a really cool guy, and I'd run into him at Amoeba buying CDs, and he's just this superstar chef that is really into this music. And then I said, hey, man, if Roscoe will play with us, will you pay him? And he said, oh, I know exactly what he'll want. And we'll pay him. It'll be great. So I asked Roscoe. And he said, yeah, that'd be great. And then we had it recorded. This concert was interesting because we had a bit more responsibility to present our music to Roscoe rather than to try to interface with his concept, if that makes sense. And that was kind of an exciting moment, because when I got to play with Cecil Taylor and things like that, you really want to get inside Cecil's music. That's the whole thing. You're trying to do that, and it's a great thing, but it's often harder in some ways because you're going outside yourself. The whole thing was that all of Sandy's playing on that album actually makes it a bit more than what it would be if it was me and Weasel. It wouldn't be bad, but I think she adds this whole other element. It's almost like an intersection of Sun Ra and AMM in a way. Working with Sandy and Weasel, these are also people that I'm friends with and I don't always like to push that, because I think one of the things folks used to always say is this is not about friendship. It should be about the music. But with Sandy and Weasel, they're definitely people I can get projects done with. So I know if I start a project with either or both of them, it's going to happen. It's going to get over the finish line, we can work together in all these other aspects of getting something done, which is why we’ve made so many albums together, things like that. In a certain way, I feel like Sandy and I have not made enough albums together for how much work we've done together. We've done some stuff that's important, but I think we could use a few more because we've just done a lot of things together. We've got a new duo that we recorded last year or the year before that, that I'd like to get out at some point. It was really beautiful and we got to some special places. And then we just recorded a couple of recent things, we just did a quartet project with Lisa Cameron, afantastic drummer, and Alex Cunningham, great violin.

LRE: This seems like Roscoe has come back to some of this long form improv.

There's been a lot of albums like Bells for Southside and Splatter, where it's almost compositional, but it's kind of exciting in a way to hear him sort of back in a real, long form kind of improv space, developing ideas over a much greater duration. I mean, I just love him. Just love him.

DS: Well, yeah. He's one of the greatest. in the Art Ensemble. I was saying that Odwalla the Juice Company is a name from the Art Ensemble, and they would pay to bring the Art Ensemble to the Bay Area every year. So I got to see the original quintet, I got to see the quartet formations, and I got to see that group a bunch of times. So they were just huge for me, and I got to see them. I saw the Art Ensemble before I was even involved in actually trying to play this music, back when I was still trying to have a Minutemen type band. One of the cool things about that Roscoe show was being able to listen to his music up until then and really dive into Roscoe Mitchell's music. One of the really exciting things is I went to my local record store in Houston, Vinyl Edge, and I found this LP. Do you guys have this one? (holds up Roscoe Mitchell, Tony Marsh, John Edwards LP Improvisations, otoroku, 2013)

(NM and LRE shake heads yes)

DS: Yeah. And that's another one where he's doing improvised music on a long form double LP with the great Tony Marsh and John Edwards, who I'm a big fan of. And so that’s kind of exciting. And in that time period, there wasn't a lot of that when I first started to do this music. If you wanted to know what the new releases were, you went to the record store and you looked.

It was one of the first times in a long time where I found an incredible album that I didn't know about in the record store that was relevant to what I was about to do. So it was a big moment to find that record, there's very few times since then.

NM: One more question on the Mitchell album. When you play with somebody like Roscoe Mitchell, who has led so many groups, and then kind of he's had all his orchestrations, he's done conducting, how does he communicate? Did you talk beforehand about what you wanted to do? You said that you were going to be more geared toward what you all play?

DS: Well, we knew that he liked the album, and that's why we asked him to play. And we didn't discuss that with him at all. He got out of stopwatch and used it a timer, and that's why it's a CD length. So I think we knew he was planning to play all the way to the end. I don't think he said it. We just knew. Maybe he said it, but there was some information whether he said it or whether it was there, that we were going to do one long piece. That was something we knew. And then when you know that, what's pretty cool is you can settle in and work with it. This goes into something that's a bit like thinking about what I think about as far as the audience. I don't ever want to compromise my music. And the kind of lucky thing for me is that's what my audience expects of me. My audience is not expecting me to please them. Right. I think you have to make these considerations about taking your music out of your bedroom and into the world. And the sculptor Lawrence Weiner, who I'm a big fan of, said you only make work for the public, so you have to think about them to a degree. One of the things I think about is that if possible, especially at a concert, my ideal concert would be a local series that has two 20 to 25 minutes sets. I think what you can give an audience is brevity if you're not working with scale. That's the way I always like to put it. If you're not working with scale, make things concise. But in this case, scale was part of it. We knew we're going to make one long piece. Right. So we know we're working with scale. And sometimes you just start working with scale. It's not discussed. It just happens. But like Feldman, when he knows he's going to write a four hour piece or whatever, he's working with that scale, he's trying to deal with long form decision making and stuff like that. And I think that's what happens in a concert, like with this quartet or recording with this quartet, we knew we were making a long form piece. We knew we're going over. We're kind of working with that time frame.

Ewen/Rowe/Smith + Gooseberry Marmalade - Houston 2012 (Balance Point Acoustics, 2021)

A terrific double CD that combines a set from the trio of Ewen, Rowe, and Smith and Ewen’s Lady Band - working under the moniker Gooseberry Marmalade here) - with a set from the trio alone. of Ewen, Rowe, and Smith. The former was recorded live at 14 Pews, and the latter a couple of days later at KUHF. Both discs are excellent, very much in the spirit of Scratch Orchestra and the more subtle AMM releases, but also very different. Despite the large group, the Gooseberry Marmalade set is measured, even pointillist, as the band works its way through several scores selected by Rowe, Ewen, and Smith. The trio improvisations, likewise, are reserved pieces of sound art that detail how differently Ewen and Rowe approach prepared guitar, smith filling in the gaps with long bowed tones or animated grima. - NM

DS: Scale is something that Keith had often worked with in AMM. Keith is really influenced by Cage and also Rothko and the abstract expressionist painters and things like that who are dealing with scale and looking at scale in that way. And one of the things I did once it came up that would be possible to play with Keith is I would go to the Menil Collection in Houston, which definitely has some of the best artworks in the world that live there. Like, there's a 60 foot long Cy Twombly painting in Houston. It's the most work of his in America, and I think the most work in one place, and it's free. You can walk in there and look at this Cy Twombly anytime you want. And so I'd go sit in front of the 60 foot long side Twombly painting for like an hour, just working on my sense of scale and my concentration on the painting, looking at the painting and things like that. This is also something that was very much driven by Sandy in a way. Keith had come to Houston to do a concert for Dave Dove’s organization, Nameless Sound. And Texas has these great things called Ice Houses where you basically sit outside and drink beer. And there's a really iconic one called the Alabama Ice House. And we were there with Keith and that Ben Patterson exhibition was up, and I had done the Ben Patterson piece, and Keith was really excited and had a duo with Ben Patterson. I don't know if there's any recordings of that, but Patterson played an electric upright duo with Keith Rowe, and Keith was really into the connections between Fluxus and Scratch Orchestra and stuff. And so we're drinking and talking about that. Sandy was there and he knew her from before, he'd been coming to Houston for a while. They've done workshops and stuff like that. And obviously Keith is the first one to really put the guitar flat and have that as the primary working method. A crucial difference, but an important difference is he tests the guitar totally flat on a table, and then he has his objects on the table, and the guitar is rigid. Right. And one of the things about Sandy is the guitar is on her lap, and she uses her legs to move the guitar and to move the objects on her guitar, so some of it is coming from her legs as well. Almost like a drummer but it's not really percussive, but it's a whole body concept. And the fact that it's on her lap is an important part of the concept. That's not obvious. Like, you might just think I was just there because it's flat but also her legs come into the movement and the rhythms and the sounds that are happening. So her hands come into it and her legs under it are moving it and I think that is an important aspect of that. And then hearing her with Keith, you can kind of hear there's a different type of movement in her playing versus his.

I found out from the Keith Rowe film What is Man and what is Guitar, one of the things I took from that film was that he first put it on the floor, which is an interesting idea. I didn't know that he was thinking about Pollock working above the canvas on the floor, and putting the guitar on the floor. There's that connection with Sandy and Keith. But then the other connection was that Sandy had made this all female ensemble that changed his name every time. And it was always a name involving fruit and they came up with a new name every time. And then they would make up their own little pieces and things like that. And it was very much in the tradition of Scratch Orchestra in a way, even though she wasn't thinking that at all, if she knew about the Scratch Orchestra, it was in passing. She was around enough hardcore improvised music nerds that knew the history that I'm sure the Scratch Orchestra was mentioned in her presence at some point, but this was all her idea, to do this group with the women. She just felt like not enough women were present on the scene. And so it was open to people who were musicians or not. They didn't have to be musicians. They just had to be interested. There was a choir in the Bay Area called the Cardew Choir. And their thing was, if you're interested, you're already qualified. Okay. So we made that connection. We asked Keith to restage some Scratch Orchestra pieces with her all female ensemble, and that sort of brought the whole thing together. And we brought a Cy Twombly book of the paintings in Philadelphia, the 50 Days at Ilium, into the studio. We used that as a graphic score, but not really. It was just there. And then I was able to get photos from the Cy Twombly Foundation, liners from Brian Olewnick, and then from Rebecca Novak.

---

1 comment:

Phenomenal interview—so much to listen to! All the art and literature reference points resonate with me. What a treasure of musical approaches!

Post a Comment

Please note that comments on posts do not appear immediately - unfortunately we must filter for spam and other idiocy.