|

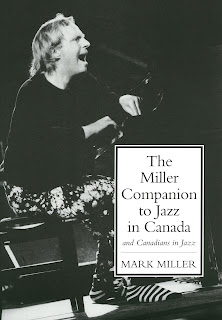

| Paul Plimley at the 2014 Vancouver Jazz Festival. Photo by Mark Miller |

The Canadian pianist Paul Plimley passed, from cancer, on May 19. It was a sudden event. He had moved to a hospice just two weeks before. Around that time, I had written a review of a remarkable recording by Paul with John Oswald and Henry Kaiser, At One Time. Before it appeared in print, John told me about Paul’s condition and asked if I would share the review with him before publication. I did. The review appeared in print the day of Paul’s death. It’s available at www.thewholenote.com and Paul Acquaro reviews the recording here as well. It’s been one of my favorite recordings of the past year, a unique revision of the act of collective improvisation.

During that interval between Paul’s entering hospice and his death, John Oswald compiled an album length anthology in collaboration with Paul. Called simply Paul Plimley, it’s available on Bandcamp and it’s the best kind of tribute from one collaborator to another, full of the rare wit that they shared. John is a highly creative improvising saxophonist and has been for about forty-five years, but he’s likely better known for his work in Plunderphonics, his term for the appropriation and deconstruction of old music and its reassemblage into the new. The program includes two of John’s pieces with Paul’s participation as pianist, radical remodellings of two very different works from the European classical tradition, one entitled Oswald's 1st piano concerto by Tchaikovsky (as suggested by Michael Snow) , which ironically begins with Paul quoting Grieg, and Para D, a reworking of Satie’s ballet score for Parade.

As strong as their musical relationship is, the relationships of Paul and John to Cecil Taylor’s music may be even stronger. Paul studied with Taylor at the Creative Music Studio in 1978-79 and managed to be the pianist on a Cecil Taylor record, playing on the orchestral Legba Crossing in 1988. John’s first venture into Plunderphonics was the construction of a kind of “Cecil Taylor Quartet”, combining solo recordings of Taylor, Steve Lacy, Barre Phillips and the late Toronto drummer Larry Dubin, a piece inspired by Michael Snow’s efforts to arrange a duet performance of Taylor and Dubin, a drummer of genius, who had died in 1978.

The most sustained piece of Paul’s solo playing on Paul Plimley, the 8-minute “Foremost”, comes from a concert at Quebec’s FIMAV (Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville) in 2000. It comes from a duet set by Oswald and Plimley that was hastily arranged when Cecil Taylor was late for an appearance at the festival, and is drawn from a three-CD document of the event, Complicité (Victo), the year’s ultimate festival concert: a set by Oswald and Plimley, an hour of Marilyn Crispell and an hour of Cecil Taylor, likely the greatest evening of free jazz piano in Canadian history (the background here is sourced from John’s extensive note to Oswald's 1st piano concerto by Tchaikovsky (as suggested by Michael Snow) which can be reached through that work’s title in Paul Plimley, at the bandcamp site).

There’s also a remarkable sample from the construction phase of At One Time, constructed from solo improvisations over Cecil Taylor recordings, in which we hear Paul playing vibraphone along with a 17-minute Taylor piano solo. Sprinkled throughout Paul Plimley are 11 short “pieces”, gem-like phrases and passages running from five seconds to one minute, 24 seconds, fleeting glimpses (snapshots, haikus, images), drawn from Paul’s solo CD Everything in Stages (Songlines)

* * *

To get more of a sense of Paul Plimley’s range, his sheer brilliance and the emotional depth of his playing, there are some other recordings one might seek out. For an easy transition, recalling Taylor’s remark that “If I was a bass player, I would want to be Barry Guy” (Good grief, I just checked google for that quote and I was the first source cited—how untrustworthy is that?!?!), the place to go is Hexentrio (Intakt, 2012) by the trio of Plimley, Guy and drummer Lucas Niggli. What can I say about Lucas Niggli’s drumming? If you constructed a machine to play drums like him, it would probably overheat and break down. The group turns out to be the perfect place for Plimley, whose spectacular creative velocity (mind, fingers) could find few optimal homes.

Paul first garnered significant attention in a duo with bassist Lisle Ellis, a group that emphasized the conversational and lyrical dimensions of his playing. I’ll single out two recordings that demonstrate those aspects of Paul’s work. One is Kaleidoscope (hat ART, 1992), on which the duo present a program of Ornette Coleman compositions, most at up-tempo but all showing Paul’s gifts where the emphases are specifically melodic and rhythmic. “Peace” might rank highly among all piano performances of a Coleman composition (not far off Paul Bley’s fine avant-funk recording of “Rambin’” recorded in 1966, on the eponymous LP). Another recording involving Ellis, in which Paul’s clarity and empathy shine through, is Sweet Freedom - Now What? (hat ART, 1995), Joe McPhee’s profound reflections on Max Roach’s civil rights-inspired works circa 1960. It’s particularly evident in the expansive, even haunted, chording of the extended “Garvey’s Ghost”; it’s equally felt in the rapid, percussive abstraction of the piano solo “A Head of the Heartbeat”, a nod to Taylor’s influence and significance as well as Roach’s message.

For a contemporaneous trio recording, the Paul Plimley Trio’s Density of The Lovestruck Demons (Music & Arts, released 1995) with Ellis and drummer Donald Robinson is very good, with a fine performance of Coleman’s “W.R.U.”

Something to suggest Paul’s significance? When Mark Miller, Canada’s most distinguished jazz chronicler, published The Miller Companion to Jazz in Canada (Mercury Press, 2001) he used one of his photographs of Paul as the cover image.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please note that comments on posts do not appear immediately - unfortunately we must filter for spam and other idiocy.