Patrick Shiroishi composes and performs nine songs for overlaid solo saxophone on the 25’ Hidemi.

Shiroishi has recently released a long string of moving statements documenting a creative boom yet I would consider Hidemi a touchstone among them. While it doesn’t showcase his breadth of technique for any single saxophone, its overlays of alto, baritone, C melody, tenor, and soprano saxophones at once convey the multi-instrumental character of his practice and an impressive compositional vision in the arrangement of their sonorities.

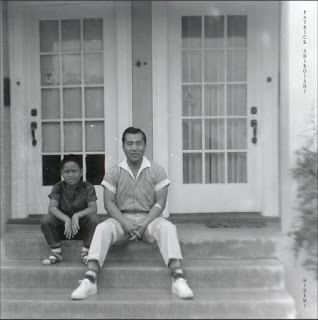

And with a throughline in Descension for solo tenor, effects, and voice, No-No / のの for alto and tenor with percussionist Dylan Fujioka, and i shouldn’t have to worry when my parents go outside for multi-instrumental arrangements with the voices of Crystal Chou and Asa Nakagawa, it is the most recent in an important thread of Shiroishi’s work that grapples with violence against Asian-Americans. These works process the generational trauma of America’s concentration camps but also more insidious and current contexts like the retaliation against Asian-Americans as a poor proxy for COVID-19 or the racist caricaturism that most recently culminated in the deaths of Delaina Ashley Yaun, Paul Andre Michels, Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Soon Chung Park, and Yong Ae Yue. Previously these subjects were briefly discussed in liners but Hidemi expands on them with an 82-page companion chapbook, Tangled, containing reflections from Asian-American musicians, including Shiroishi, Fujioka, Jon Irabagon, Kozue Matsumoto, Lesley Mok, Paul Lai, Tashi Dorji, Mai Sugimoto, Dustin Wong, Eyvind Kang, Amirtha Kidambi, Sharon Chohi Kim, Pauline Lay, Susie Ibarra, Jason Kao Hwang, Che Chen, and Rob Sato. The notes do convey that these nine songs imagine the experience of Shiroishi’s grandfather, Hidemi, after getting out of a concentration camp.

Among its nine tracks none is greater than four minutes. And this song length manifests the concision of songs from what might seem like song forms. Beyond a general melodicism, sprightly tempi, and impactful moments that stick in the memory, most of these tracks at some point feature a soloing line over a repetitive base, a kind of chorus where all lines feel active, and bridges of sometimes abruptly contrasting material. Soulful saxophone solos with the weighted cadence of despondent pause and tenderly bending sustain might evoke strong emotions but more than any one line the arrangement of them yields the catharsis. The shaking volume and ensconcing depth of their unison. Their simultaneous break from repetition into independently radiating lines. The step-pattern layering of them - three voices dropping out to silence for five to return in a kind of triumph. The building and expanding of them. Emotivity in music is an experiential thing but I imagine it would be difficult to not have an emotional reaction to the buoyant counterpoint of “Beachside Lonelyhearts,” the divergent density of “To Kill A Wind-Up Bird,” the chorus of swells of triadic spirals of “The Long Bright Dark.” And every track has its own moment of release. But it is always fleeting. Always tempered with another moment of its dissonant souring or its discordant unravelling as if to recognize and despair the trauma at the roots of the release. It is a kind of narrative of baggage in a largely non-textual music that I think is only driven home when, after Shiroishi’s one sung line translated from Japanese as ‘is this the end of the storm?’ in the notes, the final moments of the record end with hard blows in alarm just as it began. The trauma continues and it is not forgotten.

0 comments:

Post a Comment