Friday, March 31, 2023

Artur Majewski - Day 2 - Izumi Kimura, Artur Majewski, Barry Guy & Ramon Lopez - Kind Of Light (Fundacja Słuchaj, 2022) & Kind Of Shadow (Fundacja Słuchaj, 2022)

Thursday, March 30, 2023

Artur Majewski - Day 1 - Artur Majewski & Jan Słowiński - Sloma + Artur Majewski & Vasco Trilla - The End of Something (Sound Trap Records, 2022)

By Stef Gijssels

Today we review two trumpet-percussion duos with Artur Majewski on the horn, the first with Jan Słowiński on drums, and the second with Vasco Trilla. For good measure, we also add a third CD, a quartet in which Majewski equally performs.

We've followed Majewski over the years, from his earlier work with the Mikrokolektyw, with the Foton Quartet, in collaborations with other Polish artists such as Gerard Lebik, Anna Kaluza, Kuba Suchar, Rafal Mazur or international free improv luminaries like Agusti Fernandez and Barry Guy.

Artur Majewski & Jan Słowiński - Słoma (Sound Trap Records, 2022)

On the first album, the interaction between cornet and drums is as you would expect a cornet and drums duo to sound: clear sounds on the horn, rumbling drums, and strong interaction. The playing is excellent, consisting of welcoming and open-ended improvisations. The music is stripped to its core essence of two artists enjoying their and each other skills, moving together, listening, reacting. This is not genre-breaking or discovering new sonic horizons, but that is also not their aspiration.

Listen and download from Bandcamp.

Artur Majewski & Vasco Trilla - The End of Something (Sound Trap Records, 2022)

This album is definitely more daring and more exploratory, showing another side of Majewski's many artistic languages.

Listen and download from Bandcamp.

Tuesday, March 28, 2023

patrick brennan sOnic Openings - Tilting Curvaceous (Clean Feed, 2023)

Monday, March 27, 2023

Sakina Abdou - Goodbye Ground (Relative Pitch Records, 2022)

Sakina Abdou plays seven saxophone solos for alto, including a five-part suite, on the 43’ Goodbye Ground.

In 2022, the reedist also released their duo with guitarist Raymond Boni, Sources , as well as contributions to Eurythmia as a member of Eve Risser’s Red Desert Orchestra and to a realization of Michael Pisaro-Liu’s Radiolarians as a member of Muzzix. Goodbye Ground is their first solo release.

Conspicuous repetition draws the ear to its variation. Durational trills dwell on different segments of a melodic cycle, each note and set of notes developing interdependently. Intonations shift the shape of lines, in slurs, in stresses, in speeds and volumes, in extended soundings, in the disintegrating wind of overblows which peel apart the monophony to lay bare its many harmonic components rippling in the air like heat would distort it. Melodic permutations transpose the notes and stretch the cadence of sound and silence with syncope for a topological deformation or metamorphoses at scale but smaller moments remain the same enough for the recognition of repetition. While overt variations in intonation color tones in a vacuum their changing neighbors also effect the perception of them. Solo records, especially first ones, commonly present as foundational to instrument/instrumentalist identity, sometimes shorthanded as tone, and here we have a conscious, commanding play with tone itself.

Saturday, March 25, 2023

Brakophonic/Gunnar Backman

By Nick Ostrum

Guitarist, composer and producer Gunnar Backman has been documenting his wide-ranging projects on his Brakophonic label for years now. As far as I can tell, the label has released 60+ albums. Seven from 2022 are briefly reviewed here. Although this is an incomplete account of Backman’s work over the last year, it does shine light on just how curious and diverse his output is.

FLAGolodics (Lars Larsson, Fredrik Lindholm, Gunnar Backman, Anders Berg) – Happy Bappy (Brakophonic, 2022)

FLAGolodics falls on the funkier end of the prog spectrum, though it is still riddled with stutters and warped tempo changes. Driving, stadium rock backbeats and repeating laid-back bass grooves provide the backdrop. Backman and Larsson dance above it, weaving into the fabrics shredded to pieces by the other. Backman really lays in on some of these cuts, including the centerpiece, We Need Happy Peppy People. A few other tracks are more open. All in all, an interesting release that is most engaging when it deviates from the traditional song structures into less rhythmic and melodic realms.

FLAGellation (Lars Larsson, Fredrik Lindholm, Gunnar Backman, Anders Berg) – No Admittance (Brakophonic, 2022)

Although composed of the same musicians as FLAGolodics, FLAGellation has more edge. The sound is full and, especially with Lindholm’s heavy cymbal work and the omnipresent fuzz and feedback, quite heavy. The funk of FLAGoldoic is replaced by noise rock and some bitingly urgent sax runs. And, of course, there’s Backman, who often fights his way to the front with Larson, where they entangle, squeal, suffocate, shriek and squeeze until the ritual whipping is complete. Some of that violent language may be misleading, but this stands out not only in its Hendrix wonk, but also the drudgery and force that propels this album forward.

Anders Berg, Gunnar Backman - Precipitation (Brakophonic, 2022)

Precipitation is a series of short statements of echoing guitar and bass runs that vine together and diverge into interesting sonic tendrils. Often, these tracks seem like the constituent elements of potentially longer pieces: an interesting melody here, some heated interplay there. Backman and Berg clearly have a special connection, and it shows. Unlike some of the other albums in this set, however, the ideas are tantalizing but terse and beg further realization. Precipitation sounds like a series of intriguing sketches (hopefully) of a promising bigger project to come.

Gunnar Backman – Rooms Inside (Brakophonic, 2022)

As one might expect from a full (48 minute) solo album, Backman extends on Rooms Inside in a way he does not on some the shorter releases in this review. All tracks have some sort of layering and processing beyond just a pedal, but Backman is still able to explore different territories. Corridors, for instance, flirts with feedback noise and dissonance, but keeps returning to a clear guitar jangle that grounds the piece and emphasizes the tension between an almost prog-poppy order and dissolution/noise. I imagine Hendrix, Lou Reed and the show Twin Peaks (Towers, a real treasure on the album) exercised some influence over Backman’s approach to guitar, though he distinguishes himself even more in the production. Apart from a few points where phrases are deliberately clean, much of this has gone through some refraction and layering process that turns what could have come off as onanistic noodling into a glitchy and intriguing set of guitar “solos.” Backman often veers toward noise, but, even at his most disjointed, he always falls back into space rock structures and metal-inflected guitar riffage that add coherence and make this an album very much worth seeking out.

Anders Berg, Peter Uuskyla, Gunnar Backman – View-Master (Brakophonic, 2022)

This is another succinct on that speaks of a greater opus to come. However, with Peter Uuskyla, even the short pieces seem complete movements and ideas. Interestingly, the addition of a drummer seems to open space for Berg and Backman to diverge into mucky (Berg) and glimmering (Backman) territory. At other times (especially in the titular View-Master) they return to the contending interlace mode they adopted in much of Precipitation, though the machine gun rat-a-tat from the trap set propels them to new, spacey places. Much too short, but one of my favorites.

Dishwasher (Staffan Svensson, Per Anders Skytt, Gunnar Backman) – Layers//Day 1 (Brakophonic, 2022)

Dishwasher (Staffan Svensson, Per Anders Skytt, Gunnar Backman) – Layers//Day 2 (Brakophonic, 2022)

Layers//Day 1 and //Day 2 move in an even spacier, more atmospheric direction that nods toward Miles’ fusion years, though with the trumpet deemphasized. Tellingly, all members of this trio are credited not only with more standard instruments, but also electronics. Backman takes on the fretted virtual guitar and live loops, as well. The result is foggy, with Per Anders Skytt’s drums dancing in fore and Staffan Svensson’s trumpet muted but fighting its way through the haze in the back. Backman’s performance is understated and almost ambient. Still, the music has a clunkiness that lends it depth and intrigue. Also notable is the length of these releases. Unlike the bagatelles that constitute No Admittance, Precipitation, Happy Bappy and View-Master , these tracks have room to develop. Most push beyond ten minutes, and, despite their improvised nature, never get caught in the guitar-forward doldrums. Rather, they remain engaging throughout and, taken in the context of these other 2022 releases, show that Backman and company do their best when they have the space to stretch out.

Friday, March 24, 2023

Mette Henriette – Drifting (ECM, 2023)

By Troy Dostert

Norwegian saxophonist Mette Henriette released a startling debut album back in 2015, after which she more or less disappeared, at least in terms of recording, until her long-awaited follow-up, Drifting. Anyone figuring that she might use this hiatus to reinvent herself would be mistaken, however. Her sophomore release continues in the same vein as its predecessor, with an elliptical, less-is-more aesthetic in which the silences speak as loudly as the notes that are played. And the chamber trio format also remains, once again with pianist Johan Lindvall, but with Judith Hamann taking over the cello duties from Katrine Schiøtt this time around. This release may be somewhat less ambitious overall, as there is no second disc of material utilizing a larger ensemble, as was the case on the 2015 album. But maybe this is all to the good, as it allows a more concentrated glimpse of Henriette’s distinctive approach to her instrument and her spartan compositional style.

Relying on figures and sketches rather than lengthy, developed pieces, the 15 tracks here clock in at a relatively brisk 43 minutes. Several are shorter than two minutes, such as the captivating opener, “The 7 th,” which invites the listener into Henriette’s sound-world in such an unassuming manner that the moment slips past almost too quickly. Just a wisp of melody, delicately traced by all three musicians without adornment or elaboration, and then it’s over. “Cadat” is just as elusive, with Henriette’s fragile, simple phrases floating atop Lindvall’s patient upper-register musings and just the faintest high-pitched textures from Hamann.

The longer tracks do possess a certain appeal as well, especially “Oversoar,” in which Henriette and Hamann’s diaphanous excursions intertwine mysteriously alongside Lindvall’s pointillist accompaniment. And “Indrifting you” also possesses a lovely aspect, as Henriette’s lyricism finds its way above the subtle restraint of her partners. While there is no question this is an ECM recording—one can almost feel the Nordic chill emanating from the austere production only Manfred Eicher can provide—it is Henriette’s underlying warmth, particularly in the lower reaches of her horn, that prevents the music from icing over. While some listeners may have hoped to see Henriette branch out a bit and explore new terrain, Drifting remains an inviting and sometimes entrancing recording.

Thursday, March 23, 2023

The Coal - Recorded Remembered (Shhpuma, 2023)

By Gregg Miller

We have here a very successful, experimental trio sound out of Greece made up of guitarist Giannis Arapis, Dimos Vryzas on violin and effects, and Simos Riniotis on drums and resonant objects. The Coal aims at a rough melodic beauty which remains nonetheless open to the fraying at the edges beyond which lies that vast pool of undifferentiated sound from which it gathers its material. Atop most of Recorded Remembered is Arapis’s electric guitar running through delay, freeze, reverse, and loopers with occasional gain and whammy. To the miscellaneous percussiveness in all those textures and effected sounds, add in Vryzas’s moody effects, his violin, and Riniotis’s creative kit-playing and found-sound palette, and we get a collective outpouring with depth and a certain worldliness. It’s all there, intentionality and a genuine feeling for play. The eighth track, “For Lisa,” is particularly lovely: a longish, singing guitar line is joined by a mournful violin over the sound of crumpling something and asymmetrical cymbal and tom hits. Sonically less refined is track 9, “The Keys I Don’t Use,” which seems to foreground, were I to hazard a guess, the keys they don’t use. Most of the tracks are more concerned with coping than disruption, though they still feast on the entropy of the sonic rather than give in to the impulse to erase it. There are many highlights. Nothing here feels particularly technical. The feelings are all very natural and honest. On the final track, there is briefly some actual chordal work, but pay that no mind, it arrives having weathered what there is to weather. Highly recommended.

Listen and download from Bandcamp:My colleague Eyal Hareuveni provides some of the context for Arapis’s playing here.

You can catch a taste of Arapis’s solo electric guitar magic here:

Wednesday, March 22, 2023

Impressions of Taktlos

Festival Program: https://www.taktlos.com/programm

All photos (c) Cristina Marx (Photomusix)

Day 1: Friday March 17

X Ray Hex Tet

Edward George words; Paul Abbott drums, synthetic sounds; Billy Steiger

violin, celesta; Seymour Wright alto saxophone; Pat Thomas piano, electronics;

Crystabel Riley drums;

Miao Silvan Makossiri

Makossiri laptop, nyadungu (lyre); Miao Zhao

bass clarinet, electronics; Silvan Schmid trumpet, mixing desk;

DJ Diaki

DJ Diaki - laptop, drum machine;

Day 2: Saturday, March 18

Crystabel Riley

Crystabel Riley - drums;

Lotus Eddé Khouri x Gamut Kollektiv

Lotus Eddé Khouri -

composition; Binta Kopp - laptop; Marina Tantanozi - flute; Miao Zhao - bass

clarinet; Paula Sanchez - cello; Paul Amereller - drums; Philipp Eden - piano;

Silvan Schmid - trumpet; Tapiwa Svosve - alto sax; Tobias Pfister - tenor sax;

Vojko Huter - guitar; Xaver Rüegg - bass;

g a b b r o

Hanne De Backer - baritone saxophone, bass clarinet;

Andreas Bral - piano, Indian harmonium; Raf Vertessen - drums;

Day 3: Sunday, March 19

New projects, new constellations, including (though not all pictured)...

@XCRSWX (Seymour Wright and Crystabel Riley)

- alto saxophone, drums; Lotus Eddé Khouri L’anatome - movement; Pat Thomas -

piano;

Hanne De Backer - baritone saxophone; Raf Vertessen - drums; Paul Amereller -

drums; Edward George words; Makossiri - laptop, nyadungu (lyre); Tapiwa Svosve

- alto saxophone; Xaver Rüegg - bass;

Marina Tantanozi flute; Xaver Rüegg - bass; Andreas Bral - piano; DJ Diaki - laptop, drum machine; Paul Abbott - drums; Billy Steiger - violin;

Tuesday, March 21, 2023

Leo Chang & VOCALNORI

By Keith Prosk

Leo Chang released four recordings, all duos, in 2022, three of which feature the homemade instrumental system, VOCALNORI, composed of suspended Korean gongs and cymbals, voice, and electronics to convey vocal vibrations through the gongs and cymbals. A manifestation of grappling with personal identity, the voice is literally filtered through symbols of cultural context while simultaneously subverting tradition to best fit the self by using them in uncustomary ways. These three recordings all also pair VOCALNORI with piri, the Korean double reed, the texture and attack of which could recall Steve Lacy’s ducks at their most raucous or the ecstatic energies of Kim Seok-chul’s hojok, probably building from a foundation of Chang’s amPiri system, featured in the fourth 2022 recording, Some Time , with Adrianne Munden Dixon on violin and electronics. Each seems to accentuate certain aspects of VOCALNORI and considered together demonstrate a generous adaptability of the instrumentalist and instrument to diverse scenarios.

with Jason Nazary - Failure to Display (SUPERPANG, 2022)

With percussion, whose many-limbed polyrhythms of kick drum booms, shimmering crash, and marching roll fills at times appears to channel the exotic or rather extraplanetary swagger of an Arkestra drumline, the VOCALNORI seems to assume a more percussive character. Chittering, skittering metallic scat. Apoplectic arrhythmias that can resound, reflect, and interfere for brilliant walls of klang. The voice may remain recognizable in subaqueous groans or seem texturally quite close to the kit and be completely baffled by the metal. The resonant material of which lends the space a harmonic glow though this music is mostly, particularly rhythmic. Playing piri requires the air that would power the gongs but bleep bloop rhythms tend to appear where the gongs are not.

with Chris Williams - Unnameable Element (Dinzu Artefacts, 2022)

With trumpet, whose resonant metal material matches the grain of the gongs and whose mutes similarly filter and color the breath, the VOCALNORI assumes a more brassy character. Softer, slower attacks that allow gong soundings space to breath begin to lend a melodicism to the system not dissimilar to the trumpet. Bright domes’ dynamics tethered to breathing cadences. Textures can blur and I’m unsure if something that sounds like low brass, bowed cymbals, or oms is one or the other. Sometimes the system appears activated, just turned on, humming like electric current, sparsely sounding a cistern reverb for an ambient substrate upon which a soulful, smoky trumpet solo can occur.

with Lucie Vítková - Religion (Tripticks Tapes, 2022)

With accordion, synth, hichiriki, harmonica, voice, and objects, VOCALNORI seems to find a system foil. Timescales stretch, long tones (im)perceptibly breach and sink into an activated ambience, oms and moans extend into meditative and trance states, the buzz of vibrating metal and its heralding harmonic oscillations rise to consciousness in these quieter soundscapes, cut by squalls from winds only rarely. The discrete attack of the rhythm system becomes something as enchanting and unrecognizable as the voice through gongs through sustain. Though elongated tone seems to flatten dynamics and movement the invitation to discern difference on a smaller scale actually amplifies its dimensionality. And in relation to the title, the gongs return to a kind of ritual - or at least the cairns for it - while remaining unstruck as they would in the original, returning to the simultaneous embrace and resistance of cultural identity at the heart of the system.

Monday, March 20, 2023

Two Trios from Sophie Agnel

The classically-trained French pianist Sophie Agnel is known for her imaginative way of transforming the grand piano into a lively, vibrating organism with extensive preparations as well as for her collaboration with like-minded, innovative improvisers like Phil Minton and John Butcher and sound artists Lionel Marchetti and Jérôme Noetinger. Two recent releases offer her visionary, sonic imagination.

Agnel / Lanz / Vatcher - Animals (Klanggalerie, 2023)

Animals is the debut album of the unlikely, free improvising trio of Agnel, Swiss, Berlin-based turntables wizard Joke Lanz (aka Charles Testa) and American, Amsterdam-based jazz drummer Michael Vatcher. Agnel formed this trio for a performance at the Festival Météo in Mulhouse in 2016. Animals is a studio recording from Le Confort Moderne during Jazz à Poitiers in November 2018. The trio celebrates the release of this album with a European tour.

Agnel takes this trio to deliciously uncertain, heretic grounds. Lanz is a jack-of-all-trades who adds his extensive experience in playing anything, from improvised music to experimental music, from noise to turntablism, and is known as the leader of the action project Sudden Infant. Vatcher brings to this trio his experience of playing with jazz, free improvisation and avant-punk with Michael Moore, Tristan Honsinger and The Ex.

The 13 short pieces of Animals capture the wild, dadaist imagination of this trio with suggestive titles like “Laughing Hyenas”, “Lullaby For Dionysus” and “Metallic Meditation”, and often with more ironic and insightful references like the hyperactive “Michael Nyman Fell Asleep” and “Paul Rutherford's Trombone’. The dynamics are urgent and intense, creating constant, stimulating tension with unconventional and inventive techniques, but always precise ones, and with a subversive sense of humor and, obviously, many sudden twists. This trio explores radical sonic ideas, or unpredictable, rhythmic dynamics with great curiosity but no attachment. Once it is exhausted, the trio continues to its next adventure. Somehow this kind of improvised chaos makes perfect sense, and the beautiful cover artwork by Lasse Marhaug cements this trio's fascinating and joyful sonic collisions.

Sophie Agnel / Olivier Benoit / Daunik Lazro - Gargorium (Fou Records, 2023)

Agnel recorded two duo albums with fellow French guitarist Olivier Benoit (Rip-Stop, In Situ, 2003 and Reps, Césaré, 2014), who later recruited her to the Orchestre National De Jazz. She played in veteran baritone sax player Daunik Lazro's Quatuor Qwat Neum Sixx (Live at Festival NPAI 2007, Amor Fati 2009) and later recorded a duo album with him (Marguerite D'Or Pâle, Fou, 2016). Now the head of Fou Records, sound engineer and archivist of many historical free improvised meetings (and also a vintage synth wizard) Jean-Marc Foussat, has released live recordings of this short-lived trio from September 2008 at La Malterie in Lille and from April 2009 at Carré Bleu in Poitiers.

Agnel, Benoit and Lazro rely on their highly personal and unorthodox extended techniques. Agnel focuses on the inside of the grand piano and turns it into a vivid and intriguing playground, Benoit transforms his electric guitar into an abstract, and sometimes industrial sound generator and Lazro focuses on quiet, whispering breaths and long, sustained tones. The dynamics here are patient and fragile, letting the sparse, expressive percussive sounds resonate and float gently and suggest the course of the music. Each of the four pieces creates its own dream-like, sound universe but all highlight the poetic sensibility of this trio.

Saturday, March 18, 2023

Alan Braufman - Live in New York City, February 8, 1975 (Valley Of Search, 2022)

Friday, March 17, 2023

Piero Bittolo Bon – Spelunker (Chant Records, 2023)

By

Guido Montegrandi

The music on this album is about exploring. It can be described as

an extended use of extended techniques to produce an augmented language. The

music in this album is about experiencing. Piero Bittolo Bon plays a sax without

mouthpieces and most of the time without even blowing into it. As he says in the

brief interview at the end of this review he plays in negative extracting

sounds from the resonances produced by the movement of the keys inside the body

of the instrument. These sounds are then amplified and filtered in real time

through stomp-boxes and synths. It is feedback controlled and expanded, it is a

sax transformed into a set of percussion, and a flute echoes from somewhere

else.

We read in the notes from the artist's Facebook page: “This material was recorded in 2018, more or less halfway my still on-going

process of extracting challenging (at least for me) possibilities and exotic

dialects from the inside of the horn, which flourished into a whole new set of

perspectives on the instrument even when I approach it in a more "traditional"

way.”

The first piece - "game/élan" - has in its title all

the coordinates of the place we are visiting, it seems like we are listening to

a distorted gamelan but it is maybe just a game and a combination of style and

energetic spirit. What we ear are percussive sounds, whistles and blows that

gather for a moment and then scatter moving in other directions, another focus.

As the Bandcamp notes inform us “

the original recordings were edited and curated by Maurice Louca, a key

player in The Cairo and Berlin experimental music scene”.

A different section of the same recording session of

"game/élan" is presented in the third piece of the album "game/élan (excerpt)".

The other piece - "A melange" - offers a catalogue

of the different sounds that the augmented sax can produce. It opens with

cavernous and percussive sounds and electronic noises; then a flute (?) section

marked by the rhythm of the amplified keys. Another change marked by percussive

electronic sound followed by controlled feedback and the keys of the sax played

to follow a rhythmic pattern. There is a crescendo of noises and whistles and

distortions evocative of a tribal setting. The voice, chanted through the cavity

of the horn marks a finale where only feedback and clanking are left.

As Bittolo Bon declares this recordings features “the maximalist

side” of his solo set “a full arsenal of amplifiers, stompboxes, drum machines and synthesizers is

almost constantly involved in the search for some bit of music I might enjoy

in that moment: the only rules I gave myself were (and still are) no

overdubbing and no loopers allowed.” (notes from Bittolo Bon Facebook page)

It is interesting to

compare the music in this album (recorded in 2018) with its minimalist

counterpart in (mĭth′rĭ-dā′tĭz′əm) III - spelunker [un]ritual etudes (Self-Released 2022) recorded in 2021 using only acoustic instruments,

microphones and amplifiers. The intention and the techniques used are the same

but the sound is stripped to the bone and from a strictly personal point of view

even more fascinating.

In conclusion “Spelunker” is not music

for the faint of heart but if you are brave enough to enter the cave you will be

rewarded with paintings and stalactites that are worth the journey.

The album is available on

Bandcamp.

To have a closer look at the Spelunker project you can choose from

Bittolo Bon playlist on

Youtube.

We also interviewed Piero Bittolo Bon about his project and its

developments

Spelunker offers to the listeners a sound which is certainly non conventional

for wind instruments that’s why I would start by asking how did you come to

develop the idea of using the inside resonances of your instrument and the

feedback produced by microphones and amps to make music?

It was born by chance: as it may have happened to many wind players

or singers or to anyone using microphones, during a sound-check I got too close

to a microphone set to a very high gain and this microphone started to whistle.

From this event I had the insightnto try to exploit this effect to produce

sounds that I might use in an improvisatory context. I plugged my instrument

into a guitar amplifier and I started experimenting

Watching your solo performances since 2014 one can notice the expansion of

the attachment and the technology used.

Yes, my gear set up has developed a life of its own… it has started

to expand in a more or less constant way. But lately I am downsizing because

many of the attachment I’ve been using were absolutely redundant. In the

beginning I had a little box made to power simple microphone insets with five

outputs, I started big, thinking of positioning five mikes in different places

of the sax bell, of course different positions into the bell produce different

resonances but then I noticed that five mikes were far too many so I settled

with just two that, I think, make enough noise. So now this is my standard

setting.

Do you consider the instrument you play as a prepared instrument or

instead as an instrument to produce augmented reality?

Well, both answers could be true, as far as augmented reality maybe

it is more correct to talk about augmented language because this peculiar

performing mode has made me find a completely different language on an

instrument that, played in the traditional way, I am quite familiar with. There

is a deviation that was more obvious in the beginning of my search, between what

I expect from the fingering I use and the actual result. This deviation is

produced by the fact that the sounds I produce come from a negative vision of my

instrument. As a matter of fact I do not blow into my sax but I extract

resonances that are than amplified and this has brought to a different manner to

use sound. Even more, it has brought to use a very rhythmic language because I

need a quite continuous action to activate feedback. When I play in a

traditional way, my temperament is quite long-winded, I move my finger quite

fast and so I have created a language and some alternative fingering that work

quite well in this performing mode. Slowly I succeeded in creating a coherent

sound environment that I can recognize as my own and that I can really enjoy.

Has this solo work modified the way you play in more traditional contexts?

I think that the two situations permeate themselves in a quite

organic way; if you look at my Bandcamp page you will find some acoustic

recording that use the same language but without any amplification. In these

recordings I use more or less the same fingering and the same mind-set, I use

the sax without mouthpiece, I invented a way of playing it using a technique

similar to that used with the ney (a end blown flute of Persian-Turkish origin)

I use the sax almost as if it were a flute and I also use the voice speaking or

singing into it. In the end I have noticed that the material recorded is

analogue to the one produced with my electric set. Beside when I play in a more

jazz oriented context, I become aware of the fact that, at the level of muscle

memory, the suggestions of what I thought myself with this language emerge in my

way of playing.

In the Bandcamp notes for Spelunker you say that the only rules you gave

yourself were (and still are) no overdubbing and no loopers allowed; with

overdubbing you clearly loose some of the spontaneity you get with live

recording so my question is about loopers, why have you decided not to use

them?

Because I think they are a double-edged sword, I am quite prone to

indulge in my comfort zone and I think that if I used loopers, which are very

useful in many situations, I would lose some of the focus and the challenge that

this way of playing implies even from a physical point of view. It may not seems

but this continuous and percussive mode, even if I breath is not involved, is

quite tiring for the sinews and the finger muscles and this physical side would

be lost if I used loopers.

Looking at the series of your solos which can be watched on Youtube, I’ve got

the impression that Spelunker represent a snap-shot of a work in progress that

started in 2014 and is still going on?

The materials collected in Spelunker represent an halfway moment in

my solo performances because the recording dates back to 2018 ant it was a

moment in which I was using all the gears that I have (stompboxes, microphones,

synths) and the fact that I had so many sonic possibilities sometimes made it

difficult to focus on nuances. In the end I had a great number of recording and,

because of my character, I was really terrified by the necessity to make a

choice to edit the materials. If I have to choose a take of a composition

everything is easier, but when I have to choose what I like and what I don’t in

my improvisations I really don’t know where to start; it is not because I like

all of them, maybe it’s the opposite or maybe it’s because in the end they all

seem acceptable. Luckily in this process I had on my side a great friend and a

good musician: Maurice Louca who made the editing selecting the tracks and

assembled them in an order which he considered fluent and interesting

From your point of view what is the situation of improvised music in this

period?

Speaking about my solo work, I must say that I find it a bit difficult to propose it outside the jazz network of events, maybe because I am considered, and I consider myself, more internal to that network. Maybe the jazz environment is not exactly right for this music even if when I play solo I don’t fell like I’m playing something too far from what I play in a more jazzy situation. The acoustic output may be different but the intention is the same.

What about your future programmes?

I have made a couple of recording that I hope to release soon (at least not after five years like it happened with Spelunker): a solo with a very reduced setup (two microphones and two amps) which focuses on the rhythmic side of my language and a session of the duo Spell/Hunger with Andrea Grillini on augmented drums (he plays a drum set with series of sensors that control a sample library). On the more traditional side I hope to record a new album with my quintet Bread & Fox with Alfonso Santimone, Filippo Vignato, Glauco Benedetti and Andrea Grillini. I also continue my fantastic experience with the Tower Jazz Composer Orchestra, the resident ensemble of the Ferrara Jazz Club that I have been coordinating together with Alfonso Santimone since 2016.

Thursday, March 16, 2023

New - Danish - Horizons for the Piano Trio

Three Danish trios offer highly original, personal and poetic approaches for the piano trios, looking back into the rich legacy of jazz and free improvisation but also marking promising starting points for the future.

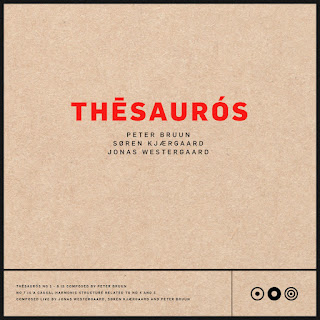

Peter Bruun, Søren Kjærgaard & Jonas Westergaard - Thēsaurós (Ilk Music, 2023)

Danish drummer Peter Bruun, pianist Søren Kjærgaard and double bass player Jonas Westergaard (who resides now in Berlin) began working together at the late nineties while all were students at the Rhythmic Music Conservatory in Copenhagen. At that time these three musicians-improvisers-composers were inseparable, beginning to shape their trio Fuschia as a collective symbiotic entity that immerses itself in the tension between complex stringent structures and improvisation.

After finishing school they parted ways. Kjærgaard started a long-running trio with drummer Andrew Cyrille and bassist Ben Street, led a Danish trio with Westergaard and a duo with legendary inter-disciplinary artist Torben Ulrich (the father of Metallica’s drummer, Lars Ulrich). Bruun joined Django Bates’ Belovèd and formed groups like the folk-pop Eggs Laid by Tigers (with Westergarrd) dedicated to the poetry of Dylan Thomas and the All Too Human, and played in the free jazz trio with trombonist Samuel Blaser and guitarist Marc Ducret. Westergaard worked with John Tchicai and in recent years with the DLW trio with vibes player Christopher Dell and drummer Christian Lillinger.

The 2016 edition of the Copenhagen Jazz Festival united Fuchsia and since then it has become an annual tradition, and Kjærgaard, now a professor at the Rhythmic Music Conservatory, Bruun and Westergaard play every year a free improvising set in the festival. But since the trio resumed rehearsing regularly, Westergaard rearranged material that was originally commissioned by the 2014 edition of Berlin’s Serious Series Festival for a septet, later released as Positioner/Positions (Ilk Music, 2021). This album marked the first part of a new trilogy of the trio.

Bruun had been working since 2018 on the music for the second part of the trilogy, the double vinyl album Thēsaurós, likely to be followed by a third part composed by Kjærgaard. Bruun has been experimenting with a concept he calls Rhythm Design which has evolved from a research project into a system of writing music with complex rhythmic patterns as skeletal forms for his composition (you can find more information. Including scores and interview in Bruun’s website). For Thēsaurós he chose three different signatures - 12/11, 12/13, and 18/17 - as an examination of polymetric structures and exploration of the potentials between the structured and the intuitive through embodiment. Kjærgaard practiced these rhythmic patterns relentlessly until they felt they were part of him. Westergaard then extracted his own bass parts from the endlessly winding piano parts. Following countless, extended rehearsals that shaped synonymous strategies of playing these intricate, labyrinthian structures, the trio ended up cutting more than 20 hours of music in the studio, with most of the takes stretching between 10-15 minutes. Seven of these extended pieces made it into Thēsaurós.

The ambitious and challenging music of Thēsaurós demands repeated deep listening in order to decipher its complex, subtle and layered structures as well as the unpredictable inner logic and mind games but it compensates with its rare, haunting and intriguing beauty. The more you listen to Thēsaurós, its music resonates more and more. The music flows naturally, keeps its positive tension, and is performed with coherence and commanding elegance. It moves freely between Nordic, chamber jazz and modern jazz ("Thēsaurō's No. 6 [18/17]: Epitome" and “Thēsaurós No 2 [12/11]: Kinesis”) to contemporary chamber music (“Thēsaurós No 4 [12/13]: Treasure”) and intuitive, free improvisation (the last, live hypnotic piece “Thēsaurós No 7: Casual Structures”), often in the same piece. This music looks back into the legacy of the piano trio but also marks a promising starting point for the future. Obviously, the music stresses a deep affinity achieved not only through the long-time connection between the old friends Kjærgaard, Bruun and Westergaard but also through long and tasking processing and immersion from every conceivable perspective, including a bodily understanding of the musical concepts, in order to achieve such a profound and coherent work.

Inspiring and simply magnificent.

Torben Snekkestad / Søren Kjærgaard / Tomo Jacobson - SPIRIT SPIRIT (Gotta Let It Out, 2022)

Norwegian, Copenhagen-based sax player (also a trumpeter) Torben Snekkestad began to work with Kjærgaard in The Living Room trio (with fellow Norwegian drummer Thomas Strønen), played with Bruun’s Unintended Consequences (Ilk Music, 2013), alongside Kjærgaard, Westergaard and Norwegian trumpeter Eivind Lønning, and continued to work closely with Kjærgaard. Last year this duo released the sublime and poetic Another Way Of The Heart (Trost, 2022). Like Kjærgaard, Snekkestad teaches at the Danish Rhythmic Music Conservatory.

Snekkestad and Kjærgaard trio with Polish, Copenhagen-based double bass player and head of the label Gotta Let It Out, Tomo Jacobson, was formed in 2016. SPIRIT SPIRIT is its debut album, released on the last day of 2022. It is a 38-minute, nine parts suite with an epilogue, edited and composed from almost three hours of spontaneously improvised studio recordings by the trio. Its dynamics correspond with Thēsaurós, as this is a democratic trio that relies on deep listening with the three musicians keep challenging each other with their highly personal and unorthodox approaches, but in a much more minimalist and sparse, introspective and enigmatic manner than the one expressed in Thēsaurós. The profound poetic interplay of Snekkestad and Kjærgaard as well as their sonic imagination informs the suggestive, austere atmosphere of this inspiring and most beautiful meeting, with Jacobson’s extended bowing techniques intensifying its melancholic, dark tones.

Paris Peacock - Wingbeats (Ilk Music, 2023)

Snekkestad (on saxophone and reed trumpet) and Bruun (on prepared tǎpan and micro percussion) return in another singular piano trio, this time with soul brother, pianist Simon Toldam (on prepared piano) in the NFT (Non-Fungible-Token) Paris Peacock, with sound designer August Wanngren and in collaboration with NFT Troels Abrahamsen. Paris Peacock was inspired by British photographer Levon Biss' super-enlarged images of insects, especially the butterfly Paris Peacock . The NFT platform offers exclusive access to supplemented content that illuminates the music and its magnifying conception in various ways through; video, essays, documentation material, as well as extended liner notes by musician/composer Simon Toldam.

Toldam refers Wingbeats to Edward Lorenz’s seminal article from 1972 about the chaos theory and the butterfly effect, reminding us that nothing in our world is set in stone and even small actions can have great power. “Now more than ever, I find it important to pay attention to details and have a genuine trust, that even small changes in our life have a severe impact on the world we are living in. To me, this mindset is similar to the art of improvised music; the very first little sound played will set the direction for the whole performance, and therefore bears defining importance,” writes Toldam in his liner notes.

The 40-minute Wingbeats was recorded live at Jazzhus Montmartre in Copenhagen and is influenced by Biss's Microsculpture of extreme, enlarged insects, and especially the image of Paris Peacock, and featuring Toldam’s Magnified Micro Music concept. Toldam drew three timelines through the image - loosely inspired by Danish electronic music pioneer Else Marie Pade. These lines travel through deep black nothings; varied colorful patterns; butterfly hair and eyes, which all are inspiringly translatable to various musical parameters; dynamics; densities; repetitions; and timbre. And beyond the more or less concrete transformation from image to sound, there's also the influence of communication between the image and our musical intuition.

The Wingbeats composition used maximally cranked microphones placed close to their acoustic instruments that were playing at a whisper’s volume in order to explore and investigate subtle sonic fields that are rarely heard, much like a magnifying glass for sound. This abstract and enigmatic composition forces you to think anew about how you listen, process this elusive sonic experience in space and time and adjust your mindset to its disorienting, sparse sounds. Obviously, your sensitivity to the most subtle, microtonal gestures and dynamics deepens and after repeated, deep listening your sonic doors of perception gather unique insights and endless other possibilities. This composition does not promise instant karma but its austere, humble and compassionate approach teaches us that even the slightest change in behavior or mindset from any one of us will have an impact on someone else, at some point. Maybe not in a week, or even a year - but perhaps in 10 years or 50 years or after we have passed on and transitioned to the eternal butterfly fields.

Free = liberated from social, historical, psychological and musical constraints

Jazz = improvised music for heart, body and mind

Popular Posts this Year

-

Les Victoires du jazz are a French annual awards ceremony devoted to Jazz . For the 2017 edition, which took place last month, all the...

-

Drawing by Anjali Grant Dear readers, Thank you for another year of being a part of the Free Jazz Collective! According to our statis...

-

Jazz (c) David Monaghan Compiling top 10 lists is a nerve...

-

Photo by Peter Gannushkin By Martin Schray Some news simply comes out of nowhere, it catches us unprepared and on the wrong foot. ...

-

By Stuart Broomer Evan Parker and Matt Wright have been working together since 2008. Wright initially contacted Parker to ex...

Tags

- *****

- 7"

- Accordion

- Acousmatic

- Africa

- Album of the Year

- Alphabetical Overview Of All CD Reviews

- Ambient

- Analog Synthesizer

- announcement

- Avant-Folk

- Avant-Garde

- Avant-garde jazz

- Avant-rock

- Balkan jazz

- Baritone Sax & Viola Duo

- Bass Bass duo

- Bass-drums duo

- Bass-Flute Duo

- Bassoon

- Big band

- Book

- Brass

- cassette

- Cello

- Cello-Bass Duo

- Cello-Drums Duo

- Cello-sax-sax trio

- Chamber Jazz

- Chamber Music

- Chicago

- Clarinet Piano Duo

- Clarinet quartet

- Clarinet quintet

- Clarinet Trio

- Clarinet-bass duo

- Clarinet-bass-drums

- Clarinet-clarinet duo

- Clarinet-Cornet Duo

- Clarinet-drums duo

- Clarinet-flute-piano Trio

- Clarinet-Guitar Duo

- Clarinet-sax duo

- Clarinet-trumpet duo

- Clarinet-vibes-bass Trio

- Clarinet-viola-bass trio

- Clarinet-violin duo

- Clarinet-voice duo

- Classical

- Concert Review

- Contemporary

- Corona Diaries

- Deep Dive

- Deep Listening

- Doom jazz

- Drone

- Duos

- DVD

- echtzeit@30

- Electroacoustic

- Electronics

- Evaluation Criteria

- Evan Parker @ 80

- Experimental

- feature

- Festival

- Festival Calendar

- Film

- Film music

- Flute-percussion duo

- Free fusion

- Free Jazz Top 10 2006

- Free Jazz Top 10 2007

- Free Jazz Top 10 2008

- Free Jazz Top 10 2009

- Free Jazz Top 10 2010

- Free Jazz Top 10 2011

- Free Jazz Top 10 2012

- Free Jazz Top 10 2013

- Free Jazz Top 10 2014

- Free Jazz Top 10 2015

- Free Jazz Top 10 2016

- Free Jazz Top 10 2017

- Free Jazz Top 10 2018

- Free Jazz Top 10 2019

- Free Jazz Top 10 2020

- Free Jazz Top 10 2021

- Free Jazz Top 10 2022

- Free Jazz Top 10 2023

- Free Jazz Top 10 2024

- Free Jazz Top 10 2025

- Fringes of Jazz

- Fusion

- General

- German Festivals

- Guitar Trio

- Guitar Trombone Duo

- Guitar Week

- Guitar-bass Duo

- Guitar-Flute Duo

- Guitar-percussion duo

- Guitar-Piano-Sax/Clarinet Trio

- Guitar-Viola Duo

- Guitars

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2010

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2011

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2012

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2013

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2014

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2015

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2016

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2017

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2018

- Harp

- Harp Trombone Duo

- Holiday Music

- Industrial

- Information Sources

- Interview

- Jazz Novels

- John Zorn Birthday Week

- Keyboard-Drums duo

- Large Ensemble

- Lonely Woman

- Mainstream

- Metal Jazz

- Minimalism

- Modern jazz

- Musicians Of The Year 2008

- Musicians Of The Year 2009

- Musicians Of The Year 2010

- Musicians Of The Year 2012

- Musicians Of The Year 2013

- My scoring system

- Noise

- Nu Jazz

- Organ

- Organ bass duo

- Organ percussion duo

- Organ Trio

- Organ-Sax duo

- Oud

- Percussion Duo

- Percussion-Vocals Duo

- Piano Bass Bass Trio

- Piano Bass Cello Trio

- Piano Bass Duo

- Piano Cello Duo

- Piano Drums Duo

- Piano Duo

- Piano Electronics Duo; Piano

- Piano Guitar Drums Trio

- Piano Guitar Duo

- Piano Percussion Duo

- Piano Trio

- Piano Vibraphone Duo

- Piano Viola Duo

- Piano Violin duo

- Pianos

- Poetry In Jazz

- Polish Jazz Week

- Portrait

- Post-jazz

- Post-rock

- Promo

- Psychedelic jazz

- Quick Review

- Re-issue

- Reeds Duo

- Review Team

- Reviewer

- Rock

- Roundup

- Sax and Electronics

- Sax Cello Drums

- Sax organ duo

- Sax Piano Bass Trio

- Sax piano cello trio

- Sax Piano Drums Trio

- Sax Piano Duo

- Sax quartet

- Sax quintet

- Sax trio

- Sax-bass Duo

- Sax-cello duo

- Sax-drums duo

- Sax-drums-guitar

- Sax-guitar duo

- Sax-guitar-drums trio

- Sax-harp duo

- Sax-organ duo

- Sax-piano-bass Trio

- Sax-sax duo

- Sax-trumpet duo

- Sax-trumpet-guitar

- Sax-Vibes-Bass Trio

- Sax-violin duo

- Serious Series

- sheet music

- Skronk

- Solo Bass

- Solo Bass Sax

- Solo Bassoon

- Solo Cello

- Solo Clarinet

- solo flute

- Solo Guitar

- Solo Oboe

- Solo Percussion

- Solo Piano

- Solo Sax

- Solo Trombone

- Solo Trumpet

- Solo Tuba

- Solo Viola

- Solo Violin

- Soundtrack

- Streaming

- String Duets

- String Ensemble

- Sunday Interview

- Sunday Video

- Techno

- Top 10 Lists

- Top 20 Free Jazz of All Times

- tribute

- Tribute Album

- Trombone

- Trombone trio

- Trombone-bass duo

- Trombone-Percussion duo

- Trumpet Duo

- Trumpet Guitar Bass Trio

- Trumpet quartet

- Trumpet trio

- Trumpet-bass Duo

- Trumpet-cello Duo

- Trumpet-drums duo

- Trumpet-guitar duo

- Trumpet-guitar-percussion Trio

- Trumpet-guitar-piano

- Trumpet-Harp Duo

- Trumpet-percussion

- Trumpet-piano duo

- Trumpet-piano-drums Trio

- Trumpet-piano-percussion Trio

- Trumpet-trombone duo

- Trumpet-trumpet Duo

- Trumpet-vocal Duo

- Tuba

- Tuba Sax Trumpet

- Vibraphone

- Vibraphone-Saxophone Duo

- Video

- Video Premiere

- Violin Trio

- Violin-bass duo

- Violin-bassoon duo

- Violin-cello duo

- Violin-drums duo

- Vocal

- Weekend Roundup

- Women In Improv

- Woodwinds

- World Jazz

- World Jazz Top 10 2006

- World Jazz Top 10 2007

(FREE) JAZZ LINKS

- All About Jazz

- All Music Guide

- Avant Music News

- Burning Ambulance

- Cardboard Music

- Diana Deutsch's Audio Illusions

- Draai Om Je Oren (Dutch)

- El Intruso

- Improvised

- Jazz And Assorted Candy

- Jazz Corner

- Jazz Frisson (Canadian French)

- Jazz My Two Cents Worth

- Jazz Viking (in French)

- Keep Swinging!!!

- Le Son Du Grisli (French)

- Master Of A Small House

- Perfect Sounds

- Scaruffi's history of free jazz

- Sound American

- The Paradigm for Beauty

- Tune Up

Blog Archive

-

▼

2023

(341)

-

▼

March

(27)

- Artur Majewski - Day 2 - Izumi Kimura, Artur Majew...

- Artur Majewski - Day 1 - Artur Majewski & Jan Słow...

- patrick brennan sOnic Openings - Tilting Curvaceou...

- Sakina Abdou - Goodbye Ground (Relative Pitch Reco...

- Brakophonic/Gunnar Backman

- Mette Henriette – Drifting (ECM, 2023)

- The Coal - Recorded Remembered (Shhpuma, 2023)

- Impressions of Taktlos

- Leo Chang & VOCALNORI

- Two Trios from Sophie Agnel

- Alan Braufman - Live in New York City, February 8,...

- Piero Bittolo Bon – Spelunker (Chant Records, 2023)

- New - Danish - Horizons for the Piano Trio

- Magnus Granberg - the intensity of haunting stillness

- Catching up with Gebhard Ullmann (Part 2 of 2)

- Catching up with Gebhard Ullmann (Part 1 of 2)

- Free Jazz Blog on Situation Fluxus

- Sundial Trio - IV (Alpaka Records, 2022)

- Günter Baby Sommer & Raymond MacDonald – Sounds, S...

- Marc Ducret - Palm Sweat: Marc Ducret Plays the Mu...

- Mu Quintet - Summit (DIRTH, 2022)

- Ivo Perelman - Molten Gold (Fundacja Słuchaj, 2023)

- Two from Joëlle Léandre

- Wayne Shorter (1933 - 2023)

- Joseph Petric – Seen (Redshift Records)

- g a b b r o - The Moon Appears When The Water Is S...

- Pedro Alves Sousa, Rodrigo Pinheiro & Gabriel Ferr...

-

▼

March

(27)

.jpg)